Art Collectors Predict "Stampede" to Cuba

Originally Published by the Wall Street Journal 2014

http://www.wsj.com/articles/art-collectors-predict-stampede-to-cuba-1418946548

Art Collectors Predict ‘Stampede’ to Cuba

With the U.S. and Cuba restoring diplomatic ties, some art-world cognoscenti are betting that the tiny island could become the next hot corner of the global art market

By Kelly Crow

With the U.S. and Cuba restoring diplomatic ties, some art-world cognoscenti are betting that the tiny island could become the next hot corner of the global art market.

Collectors in the U.S. have been circling - and collecting - Cuban art for years, thanks to a little-known exception to the U.S. trade embargo with Cuba that makes it legal for Americans to buy Cuban art, which the U.S. government classifies as cultural assets (unlike, say, rum or cigars).

Now, collectors like Miami’s Howard Farber say they expect American art lovers to “stampede” to Cuba’s

studios and galleries as soon as it becomes easier

for them to travel and shop there. “I believe Cuban

art has been a best-kept secret among a few

collectors,” Mr. Farber said, “and now that Cuba is

opening up to us I think more people will discover a genre that’s fresh and great.”

expect American art lovers to “stampede” to Cuba’s

studios and galleries as soon as it becomes easier

for them to travel and shop there. “I believe Cuban

art has been a best-kept secret among a few

collectors,” Mr. Farber said, “and now that Cuba is

opening up to us I think more people will discover a genre that’s fresh and great.”

Prices for Cuban art began climbing during the recession, driven by collectors like Mr. Farber and Miami-based philanthropist Ella Cisneros as well as major museums like London’s Tate. Currently, prices for works by Cuba’s living art stars like Yoan Capote, Carlos Garaicoia and the conceptual art duo Los Carpinteros swing between $5,000 and $400,000 apiece.

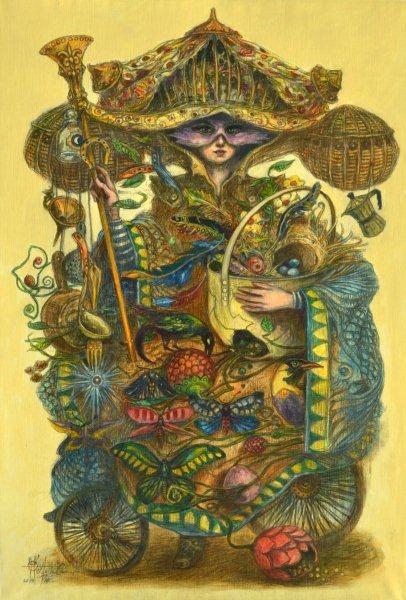

Cuban art embodies a mix of Spanish, African, and Caribbean influences and motifs. Wifredo Lam, who died in 1982, is considered Cuba’s Picasso; Sotheby’s sold his 1944 work, “Ídolo (Oya/Divinité de l’air et de la mort),” for $4.6 million two years ago, a record price for the artist.

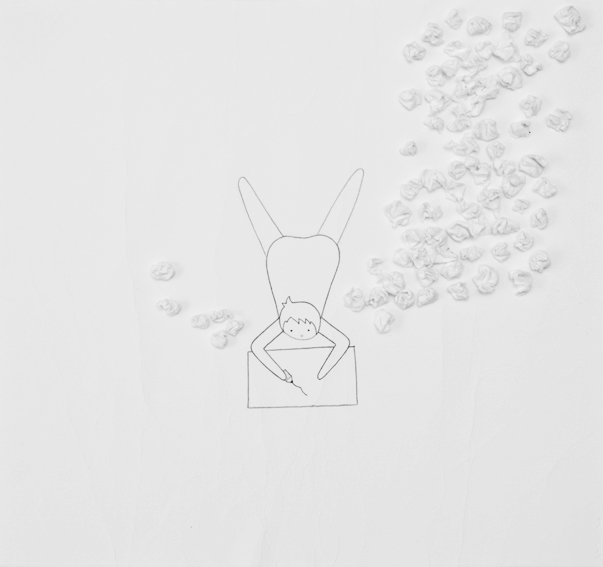

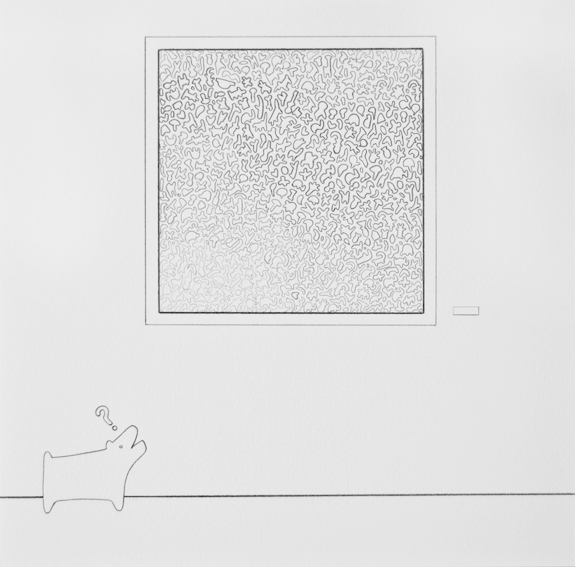

Cuban artists tend to favor found objects like weathered woods and scrap metals. Cuban art also has long addressed themes specific to the island, such as isolation and the sea: Rafts, towers and oars are frequent symbols. Political criticism tended to be depicted in coded imagery to sidestep censors; lately, more art has tried to address global concerns like immigration and the economy.

Miami collector Steven Eber said he plans to keep an eye on Cuban art to see if its artists experiment with different motifs should closer ties to the U.S. give them greater

access to the Internet and permission to travel more widely. “How many paintings of boats do we really need?” he said, half-joking.

Dealer George Adams said the art scene also will need to stand up on its own merits after its “forbidden fruit” allure falls away.

Right now, works by Cuban artists aren’t necessarily less expensive in Havana than in New York or London. But collectors who visit the island can meet and form relationships with artists there that may result in small discounts or first dibs on new pieces—before the artists’ works reach galleries in Europe or New York. This type of access is particularly valuable for Americans competing with European and Latin American collectors who have been traveling to Cuba for years. Cuban dealers say Americans currently make up more than a third of their buyers.

New York dealer Sean Kelly, who represents Los Carpinteros, said he expects American collectors to focus on finding and visiting younger, edgy artists in Cuba who might not yet have been widely shown abroad. He said collectors also likely will crowd the next star-making biennial in Havana in May.

“If you’re the 24-year-old Jean-Michel Basquiat of Cuba, nobody in the U.S. has been able to discover your work. Now, we will,” Mr. Kelly said.

Mr. Kelly also thinks it could become easier for artists in Cuba to get permission to travel to the U.S.—still a difficult task now—and sell their work to Americans wielding U.S.-based currency and credit cards.

Getting into Cuba to shop has long been a tricky proposition. For decades following Fidel Castro’s 1959 communist revolution, collectors wishing to travel to Cuba needed a travel license from the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, which doled out a handful of licenses a year to Americans seeking to scout Cuba for “informational materials” like art.

Other collectors took advantage of different legal loopholes to get into Cuba to shop for art. The Treasury Department, for instance, agreed to issue travel permits to Americans who pledged to do humanitarian, scholarly or religious work in Cuba.

Mr. Farber, who made his fortune as co-owner of

the Video Shack chain, sees parallels between the rebellious art made in China following the Tiananmen Square protests and art made during pivotal periods in Cuba’s revolutionary history. To gain access to Cuba’s art studios, he had to set up a charitable foundation five years ago and create an award for Cuban artists. Now, he owns more than 200 works and plans to go again next month.

Mr. Farber, who made his fortune as co-owner of

the Video Shack chain, sees parallels between the rebellious art made in China following the Tiananmen Square protests and art made during pivotal periods in Cuba’s revolutionary history. To gain access to Cuba’s art studios, he had to set up a charitable foundation five years ago and create an award for Cuban artists. Now, he owns more than 200 works and plans to go again next month.

Mr. Kelly is leveraging his educational license to fly his immediate family to Havana next week to attend the Dec. 28 wedding of one of the members of Los Carpinteros, Dagoberto Rodriguez Sanchez. “For Cuba,this is equivalent to Berlin’s Wall coming down,” he said. “We’re all ready to party.”