Valuing Cuban Art

Originally published in the April 2015 issue of Trust and Estates Magazine

Valuing Cuban Art by Alex Rosenberg and Leslie Koot Art, Auctions & Antiques Report

While the quality and desirability of Cuban art has been apparent to sophisticated collectors for quite some time, recent developments in restoring diplomatic relations between the United States and Cuba are spiking the interest in Cuban art among a whole new group of American art buyers

and sellers.

Howard Farber, Ella Cisneros and Rosa de la Cruz in Miami were early prominent collectors, while Shelley and Donald Rubin, founders of the Rubin Museum of Tibetan art in New York, have amassed a considerable collection of contemporary Cuban art in more recent years. With the upcoming Havana Biennial in May 2015 and the easing of travel restrictions, a new wave of American collectors is expected to travel to Cuba and acquire Cuban art.

Estate-planning professionals whose clients collect art will need to familiarize themselves with a unique set of opportunities, as well as possible pitfalls, when advising their clients on valuations of Cuban art. Both established and new collectors will haveto face decisions regarding passing on their collections to heirs and/or donating artworks to tax-free institutions, requiring collectors to determine the fair market value (FMV) of this art for Internal Revenue Service purposes.

A Brief (Legal) History

Rather than talking about the discovery of Cuban art, a more fitting term, perhaps, is “re-discovery.” Back in 1944, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York featured the groundbreaking exhibition Modern Cuban Painters, inspired by a visit to Cuba by its then- director, Alfred Barr Jr. Nearly all of Cuba’s avant-garde (Vanguardia) artists were represented in the show, including Amelia Peláez, Carlos Enriquez and Victor Manuel. It led to wide critical acclaim and purchases of artworks by important collectors, as well as MoMA for its permanent collection, most notably, “The Jungle (1943),” by Wifredo Lam.

With the exception of Lam, who already enjoyed an international reputation at the time of the breakout show and split his time between Havana, Paris and New York, the other Vanguardia painters, who were based in Cuba, quickly disappeared from collectors’ radars following Cu- ba’s

revolution in 1959. The United States broke off diplomatic relations soon after, and on Sept. 4, 1961, Congress enacted the Foreign Assistance Act, authorizing a total embargo on all trade between the two countries, including art, and imposing strict travel restrictions.

Art Exempt

It would take nearly 30 years for the free exchange of Cuban art to be restored. In 1989, a Florida–based Cuban art dealer successfully sued the federal government for the return of his Cuban art collection, previously confiscated from him, on the grounds that he had violated the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA) of 1917.1 The dealer cited the Berman Amendment, enacted in 1988, which clarified that the President’s powers under TWEA were subject to an exemption, excluding “informational materials” from trade sanctions. Although the language in the amendment included books as an example of informational materials, it failed to specifically mention works of art. The court, however, ruled that informational materials did include original paintings and that they were, therefore, exempt from the import prohibited under TWEA.

It would take another action, headed by the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee (NECLC) in 1990, to solidify U.S. citizens’ rights to legally obtain Cuban art. A lawsuit was filed against the George H.W. Bush Administration for banning the free exchange of art in violation of the 1988 Berman Amendment and the First Amendment, arguing that paintings were as much a part of the First Amendment as books. Prominent figures in the U.S. art world, including scholars, museum

directors, art dealers and major auction houses supplied their signatures in support of the suit.The court ruled that paintings and

drawings were indeed exempt from the embargo and that denying their free exchange was a violation of one of the most respected rights of U.S. citizens. Following the ruling, the Treasury Department agreed to issue new regulations exempting Cuban art from any general trade embargo. Art dealers and collectors who already had ties to Cuba started taking advantage of this newly sanctioned opportunity, but the trade in Cuban art remained a little-known exemp- tion among most mainstream collectors and, with significant travel and other restrictions still in place, a difficult undertaking, until the recent changes in government policy.

The Artists

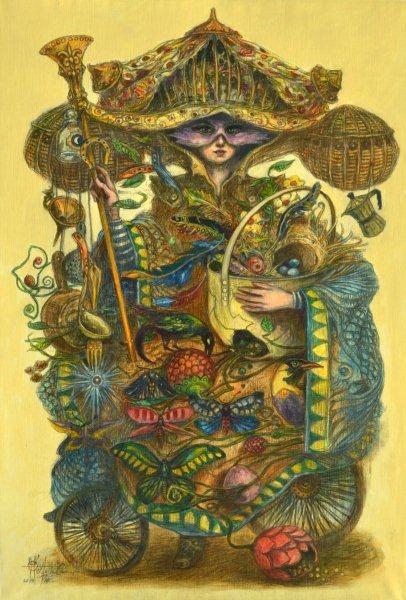

In the meantime, while U.S. interest in the Cuban Vanguardia artists had largely faded and knowledge of contemporary artists was largely absent, a new generation of artists had emerged in Cuba, straddling the influences of their Vanguardia predecessors and contemporary issues. The first Havana Biennial was inaugurated by Cuba’s Ministry of Culture in 1984 and, with every subsequent event, provided an important platform for artists, such as Manuel Mendive, José Bedia and Tomás Sánchez, who through their veiled references and tongue-in-cheek texts, commented on the everyday realities of post-revolution society, not shying away from criticisms. As a result of this exposure, a number of artists were invited to exhibit internationally, although not in the United States.4 Both Bedia and Sánchez are now based outside of Cuba, selling successfully at auction and through art galleries.

During the late 1980s, the Soviet Union’s support of Cuba ceased, contributing to extreme economic hardship, a time Cubans refer to as the “special period.” Hunger and absence of basic goods and materials were part of daily life. From this environment of scarcity, some of the most evocative and soon to be best known contemporary Cuban artists emerged: Belkis Ayón, brothers Ivan and Yoan Capote, Roberto Fabelo, Carlos Garaicoa, Kcho, Sandra Ramos and a group called Los Carpinteros were incorporating found and recycled items in their work and managed with minimal materials and ingenuity to express themes of discontent, using coded imagery. Many of these artists now exhibit and sell internationally, at ever-increasing

prices, and a new generation is fresh on their heels, eagerly awaiting the opportunity to show their work to a larger group of U.S. collectors, as recent developments promise to provide.

Problems in Valuation

Authenticity. Because of the lack of communication between Cuba and the outside world, the trade in dubious Modern Cuban art is thriving. The Vanguardia artists are all deceased, and (museum) experts in Cuba are difficult to contact. Some fake works are painted in the style of Vanguardia painters. Others are flagrant copies of works by these and other artists that may be on view at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana, but unknown to most American collectors. Especially in the Florida area, a significant number of collectors are suspected of unwittingly holding inauthentic works in their collections, often accompanied by fancy but worthless certificates. Even in the New York area, a simple Internet search for “Cuban art authentications” yields a supply of firms that promise to provide so-called “Certificates of Authenticity.” Estates of art collectors could be potentially faced withpaying estate taxes on these works, requiring the help of an objective professional to determine authenticity. There are, in fact, excellent authenticity experts practicing in Cuba, although they’re few. But, unless an appraiser has established local relationships, these experts are difficult to locate

and contact.

Patrimony regulations. Although U.S. regulations allow importation of artwork into the United States, when purchasing art in Cuba for exportation, several procedures need to be followed. During the years the Soviets were involved in Cuba, it’s believed that many important works of art were sold to foreign buyers, at prices far below market value. Today, with the developing expertise of appraisers, this loss of patrimony is virtually impossible if legal channels are followed.5 A seller of art in Cuba needs to provide the buyer with the proper documentation that allows the art to be exported. This procedure is necessary to ensure that a valuable piece of Cuban

patrimony isn’t smuggled out of the country. If the seller can’t provide an export permit,

proper documentation for the art needs to be obtained from the Registro Nacional de Bienes Culturales (National Registry of Cultural Goods) and Centro de Patrimonio Cultural (Center of Cultural Heritage) in Havana. If these institutions rule that the subject work of art is part of national patrimony, they won’t issue an export certificate, and the work may not leave Cuba. The value of Cuban art may be greatly compromised if it was exported illegally from Cuba. A certified and experienced appraiser won’t value an object unless certain questions regarding legal ownership, authenticity and provenance have been satisfactorily answered. When in doubt, the appraiser will contact the appropriate local experts and authorities to ensure that correct procedures were followed. This ethical requirement helps ensure that forged or illegally obtained art won’t be traded.

Lack of sales information. Only a handful of contemporary Cuban artists have international auction records, and often, prices achieved there aren’t representative. The primary work by these artists is mostly sold at the gallery level, leaving only their secondary work to be sold at auction. Valuing the art by emerging Cuban contemporary artists is even more complicated and requires consultation with experts who have close contacts with local Cuban galleries and auction venues to determine FMV.

Quality. With the new wave of U.S. collectors expected to crowd Cuba’s artist studios and galleries, eager to scoop up the latest contemporary star, issues of quality will, no doubt, emerge. Almost invariably, current successful Cuban artists graduated from Havana’s prestigious San Alejandro or Instituto Superior de Arte art schools, following rigorous training. A larger audience isn’t expected to seriously affect the quality or prices of their work in the short term, as they already mostly sell all the work they produce. However, me- diocre, lesser trained artists are expected to tailor their art to satisfy a much larger and less sophisticated audience to sig- nificantly boost their sales and prices. But, prices paid in Cuba can’t be automatically translated to FMVs in the United States, making the need for connoisseurship even more urgent.

A Promising Future

Cuban art promises to be the next point of focus of the international art market, offering exciting opportunities for both U.S. collectors and Cuban artists. It’s expected to take years, however, for a fully free flow of information and cooperation to be realized between the two nations and to establish essential reference systems, such as verified auction sales databases and catalogs of confirmed works of the Vanguardia and other major artists. Until that time, caution is warranted in valuing Cuban art, and the assistance of qualified, objective

experts indispensable.

Endnotes

1. Cernuda et al v. Heavey, et al., 720 F. Supp. 1544 (S.D. Fla. 1989).

2. Author Alex J. Rosenberg, then active as a private art dealer and member of the Executive Committee of the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee, solicited these signatures.

3. Dore Ashton v. Newcomb, et al., Case 90-03799-LLS (S.D.N.Y. 1991).

4. G. Gelburd, “Cuba and the Art of Trading with the Enemy,” Art Journal (Spring 2009), Vol. 68, No. 1, at pp. 26-31.

5. Alex J. Rosenberg, “The Role of the Appraiser in Preserving Patrimony,” An Approach to Advanced Problems in Appraising, with a Special Focus on Cuba, American Friends of the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba (New York 2011), at p. 205.