Hillary Gruenberg "Gratitude"

Lois Lambert Gallery presents Gratitude, a compilation of 20 years of work by Hillary Gruenberg including oil paintings, books, works on paper, and her latest work: paintings on silk, taffeta and satin.

Hillary’s work comes from the unconscious; and her focus is primarily on the process, not the final outcome. There is a genuine awareness that occurs from this unconscious state. “Gruenberg is the conduit not for messages, but for apparitions”, (Art Critic, Peter Frank).

“For Hillary Gruenberg, the world is a web of things. Images, presences, and effects interface with one another in dense networks, sometimes translucent, sometimes opaque, sometimes flat, sometimes collaged, always hovering on the verge of concretion but never quite regimented enough to fix themselves visually. There is always some other line, some other texture, some other formulation making sure to thwart the emergence of a narrative per se; recurring motifs serve to disperse rather than construct meaning, constantly proposing different, contrary relationships. Even the simplest icon — a human face, a common object — floats free of confining context. Gruenberg never lacks for lucidity or coherence, but what she brings to the picture teases us with the promise of a story that, finally, evades us, its components arrayed and layered and patterned in ways that emphasize picture, even moment, over account.

For this installment, Gruenberg’s four groups of work presented here all date from the past ten years; they overlap in production, but in little else save the spirit of the artist herself. Earliest is a series of relatively large canvases populated by a variety of motifs, most notably looming clocks and a veritable cascade of hands — or, more accurately, fingers, as often as not detached from any palm (but still tending to cluster). These devices rest in a curiously expansive quasi-landscape space that renders absurd the obdurate objecthood of clockface and digit alike. The occasional appearance of an interior space of some kind introduces another level of incongruity. Restless and unsetlled, described in line rather than modeled the images conform to a cartoon kind of vision, one hilarious and ominous by turn. In its breadth and bumptiousness this work has a Pop Art quality — closer, however, to the painterly, humanistic Pop of early ‘60s Peter Saul or David Hockney (among others) than to the cool affectlessness we generally associate with the style.

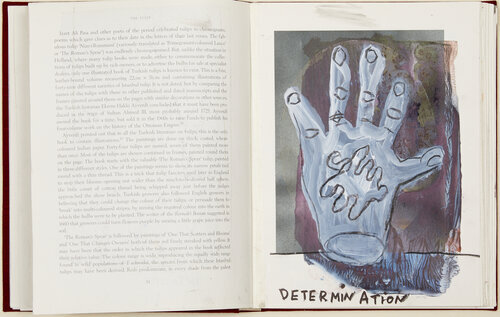

Gruenberg’s work with books has been twofold, producing bound sequences of drawings and, by contrast, taking pre-extant volumes and altering them , transforming text and image alike into paintingcollages on paper. The bound sequences can be considered a subset of her overall drawing activity, but the intervened books constitute a whole other creature. They can be regarded as Gruenberg’s homage to the pleasures of reading and intimate looking, that is, to the handheld page. She transforms image and text alike into a no-longer-legible but optically sensuous space, not the space of painting but the space of literature — even the space of the illuminated manuscript. Gruenberg is certainly not the first modernist to recycle books in this manner, but there is a gentle urgency and poignancy to her reworking that signals an awareness of the book’s perilous existence in the digital age. Here, she joins other book artists in arguing for the liberation rather than the extinction of the book, demonstrating that, altered or fully fabricated, the book has a new, post-indexical life as an art form.

Gruenberg’s other work on, and otherwise with, paper supports this “paginated” reasoning. But, as noted above, sequence here, across discrete pages or sheets, manifests the evolution of imagery rather than the articulation of meaningful events. Each drawing or watercolor or collage claims its own integral contextualization, no matter how many images it might share with its companions. These are variations on a theme (or cluster of themes), not developments of leitmotifs; indeed, they feel pianistic rather than operatic.

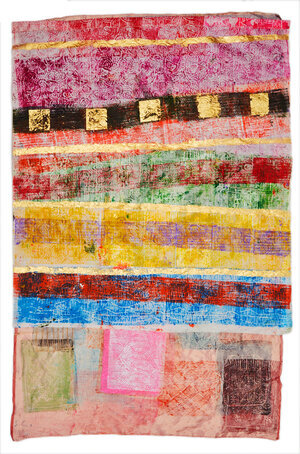

The most recent work to preoccupy the artist brings her to a new format, even medium, altogether — fibrous, weaving-like paintings realized as large banners. Here, Gruenberg is thinking in a new way about texture, color, composition, material, and even physical space, displaying these textiles as free-hanging objects. The newfound textural quality has redounded on Gruenberg’s imagery as well; the fanciful references to the real world are all but subsumed into patterned patchworks, evocative of various decorative and ritual traditions — Tibetan, West African, Andean, aboriginal Australian, and so forth. The knowing eye is likely to find associations Gruenberg herself did not incorporate, but that’s all to the better: these weavings are meant to work both as self-referential abstractions and as syntheses of human vision, honoring rather than directly imitating the various languages of the eye.

If Hillary Gruenberg has no “story” to tell, she has many sensations to provoke. Hers is an art of spontaneous response crafted into stable aesthetic form(s), sensitive to the stew of the subconscious rather than the logic of the conscious and, by contrast, to formal rather than pictorial strictures. As such, ever the Neo-Modernist, Gruenberg conflates two prime currents in modernism, the atavistic — childlike, surreal, rooted in the subconscious — and the formalist — structured, self-aware, in search of coherent order. The child has not been tamed, but she has been trained.” –– Peter Frank

Hillary studied at Otis College of Art and Design and has been awarded a grant from Women Painters West. She is also a student of Tom Wudl in Los Angeles.